Father Peter Whelan

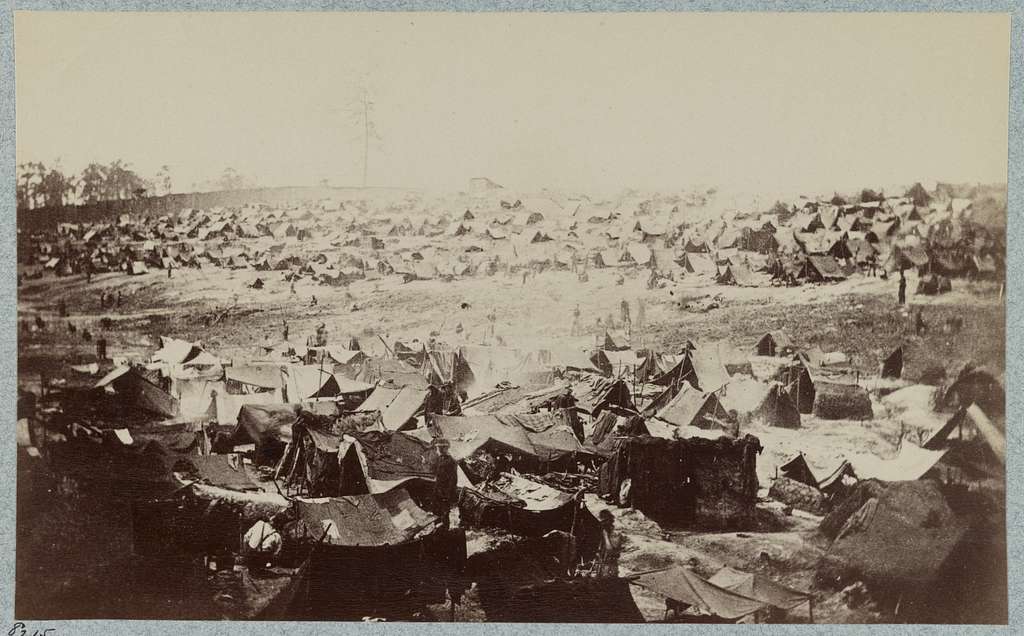

“As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us. Before us were forms that had once been active and erect; - stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness: “Can this be hell?” “God protect us!,” and all thought that he alone could bring them out alive from so terrible a place.

In over 200 years of priests receiving an education at St Kieran’s College, vocations have been undertaken all across Ireland and the world. However, none are likely to match the impact and legacy of Father Peter Whelan, who took his ministry to the American South, the depths of the Civil War and eventually as chaplain at the infamous Andersonville Prison.

From placing himself at the forefront of establishing Catholicism in Georgia and the Carolinas, being taken as a Confederate prisoner of war in New York and answering the call to assist the scores of Union troops being held in the nightmarish conditions of the prison once labelled the ‘Hell Gate’, his work granted him a rare place of respect and reverence on both sides of the bitter conflict.

Born in 1802 in Loughnageer, County Wexford to a farming family, little is known about his early life, aside from the fact that he attended St Kieran’s College from 1822 to 1824, receiving a classical and mathematical education.

Despite his eventual entry into the priesthood, he did not receive ecclesiastical training at St Kieran’s, so it's possible that his studies took place at the Burrell’s Hall school on James Street rather than the seminary at Birchfield College.

The president of Burrell’s Hall during the time that Whelan would have attended was Rev Nicholas Shearman of High Street, who later laid the foundation stone of the current St Kieran’s building in 1836.

The precise time that he left Ireland for the newly formed Diocese of Charleston isn’t known, but he was ordained in the city in November 1830 and was said to have celebrated the first ever mass in Raleigh at the house of a Presbyterian in 1832.

After several years of carrying out his duties in communities around North Carolina, Whelan became the pastor of a church near modern-day Sharon, Georgia in 1837, a parish which was the first planned Catholic community in the state.

He would spend nearly 20 years there, before being called to Augusta to provide assistance during a yellow fever outbreak and take on the duties of Fr Gregory Duggan, also from Wexford, who had fallen ill.

Whelan was eventually summoned to Savannah where he took on the role of administrator for its entire diocese and would stay for the rest of his life.

Against the backdrop of the Irish priest’s work at the head of the church in Georgia, the fragile Union between north and south came apart at the seams, with tensions erupting into civil war in April 1861.

Georgia had been the fifth slave state to secede from the Union, joining the Confederate States of America in February of that year and began the path towards ministries the likes of which Whelan could never have imagined.

His first taste of warfare came after he volunteered to serve the needs of Catholic troops, particularly the Montgomery Guards which were almost entirely comprised of Irish soldiers, stationed at Fort Pulaski outside Savannah.

Now 60, Whelan was trapped at the fort when it was encircled by Union troops who began a 112 day siege in early 1862 and his poor luck led to him becoming one of the few priests to come under direct, heavy fire from the enemy.

After a 30 hour bombardment, the fort was surrendered by its commanding officer, Colonel Olmstead, and although Whelan was offered freedom as a non-combatant, he chose to remain with his congregation as they were taken as prisoners of war.

The men of the fort were transported to Governor’s Island, New York where poor conditions led to many suffering from pneumonia, typhoid and measles.

By corresponding with New York City priests, Whelan was able to secure improved provisions and was granted parole due to his advanced age, but again chose to remain alongside the men, endearing him to soldiers of many denominations within their ranks.

After a prisoner exchange in July 1862, all were returned to Savannah, but even after navigating the ordeal, Whelan was still to observe an even greater human catastrophe.

On his return to Georgia, he resumed his post of Vicar General and the administration of church affairs. By 1864, the tide of the war had turned against the Confederacy and the march of General Sherman loomed.

As fighting came closer to the Confederate capital at Richmond, many prisoners were moved south into increasingly overcrowded stockades.

The most notorious of these was located at Andersonville, which held 33,000 men at its peak in an open-air space designed to hold 10,000. When a passing priest noted the large number of Catholics imprisoned and observed the horrific conditions, the Bishop of Savannah asked Whelan to travel to the prison to minister where he arrived in June 1864.

Speaking at the trial of Captain Wirz, the officer in charge of prison affairs, in Washington after the war, Whelan testified positively in favour of the defendant but described the scale of death at the prison saying; “The prisoners looked, some of them, very emaciated. I cannot tell you how many dying persons I have administered spiritual aid to. Perhaps it might have been fifteen hundred or two thousand.”

Image: Rows of ramshackle tents in the open-air at Andersonville Prison. Source: Library of Congress

Of the 45,000 Union soldiers that came through Andersonville over its 14 month existence, nearly 13,000 died, mainly of scurvy, diarrhea and dysentery. The prison had an inadequate food supply and the only source of drinking water also acted as a latrine leading to rampant spread of disease among prisoners.

Whelan lived about a mile away and worked from dawn to dusk for four months. Other priests assisted in brief spells but could not endure the hellish conditions leaving him as the only permanent chaplain to the prisoners during the hot summer, the period of the year with the highest mortality rate.

His constant presence and assistance earned him the same high standing among the Union captives as he had gained with his own rebel comrades as prisoners of war in New York two years earlier.

As a staunch secessionist, it’s hard to imagine that Whelan was an opponent of slavery in the south, but he did not discriminate when it came to his ministry, providing guidance to those of all religions and both black and white federal soldiers.

“Ideologically he was a very strong Confederate but he didn’t really see sides when it came to Andersonville,” says Dr Howard Keeley, Director of Georgia Southern University’s Center for Irish Research and Teaching.

“It’s probably the single greatest human disaster of the Civil War and it’s fascinating that the horror there directly precipitated the creation of the American Red Cross, it’s an extraordinary blight on the state of Georgia.”

“That was really a kind of almost fatal decision on his part. He was very committed to advocating for those who are essentially powerless and the victims of larger movements like war,” Dr Keeley adds.

The fatal decision being referred to is a lung condition, likely tuberculosis, that Whelan contracted as a result of his time in the squalor of Andersonville. Despite his declining health, he managed to undertake a vital act of charity after his departure from the prison.

The priest borrowed $16,000 in Confederate money, the equivalent to $400 in gold, and used this to buy ten thousand pounds of wheat flour which he had baked into bread and distributed at the prison hospital.

SEE ALSO: Kilkenny senator tables bill on domestic violence

This became known as Whelan’s Bread, providing months worth of rations to the captives and leading to him gaining the moniker of The Angel of Andersonville, undoubtedly saving many hundreds of lives in the process.

The Union soldiers remembered Whelan in their diaries and memoirs with Henry M. Davidson of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery describing the importance of his work in the stockade.

“Many and many a time I have seen him thus praying with the dying, consoling alike the Protestant and the believers in his own peculiar faith. His services were more than welcome to many, and were sought by all, for in his kind and sympathizing looks, his meek, earnest appearance, the despairing prisoners read that all humanity had not forsaken them”.

Though Whelan’s health never fully recovered after his time at Andersonville and the surrender of the Confederacy, he continued his work in Savannah and even publicly criticised Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War in the Lincoln administration, over the difficulty in being reimbursed with the money he had borrowed for the flour.

His condition continued to deteriorate and he administered his last baptism on January 15, 1871 before dying on February 6 at the age of 69. Whelan’s funeral procession was the longest ever seen in Savannah, which included mourners of multiple faiths and soldiers who he had accompanied as a prisoner of war.

The Savannah Morning News reported that “one prominent feature in the funeral cortege could not escape notice. It was the late garrison of Fort Pulaski, together with the Confederate soldiers and seamen who had been the recipients of Father Whelan’s love, affection and sympathy.”

A crowd gathered at Whelan’s graveside to commemorate his 150th anniversary in 2021, showing the enduring nature of his legacy, and while his deeds in Georgia and the Carolinas are well documented, his early life in Wexford and Kilkenny is still being uncovered.

“The two main unknowns are why did he go to Kilkenny, which is something we’d like to tease out and how did he get to Charleston? What specifically caused him to hear of those opportunities?” asks Dr Keeley, whose research into Whelan is ongoing.

“That would be a real breakthrough to have a sense of how he ended up in Kilkenny as there would have been options available to him that might be closer and cheaper,” he concludes.

With relatively recent findings such as a namesake nephew who likely travelled to abroad with him, to the chance discovery of his homeplace in Wexford some years ago, the story of how Father Peter Whelan went from being a student in the streets of Kilkenny to the heart of the bloodiest war in American history may yet be revealed.

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.